How Seat-Belt Promotion Works

Seatbelt promotion works. But how well?

60% of drivers still don’t use seat belts (and even more passengers).

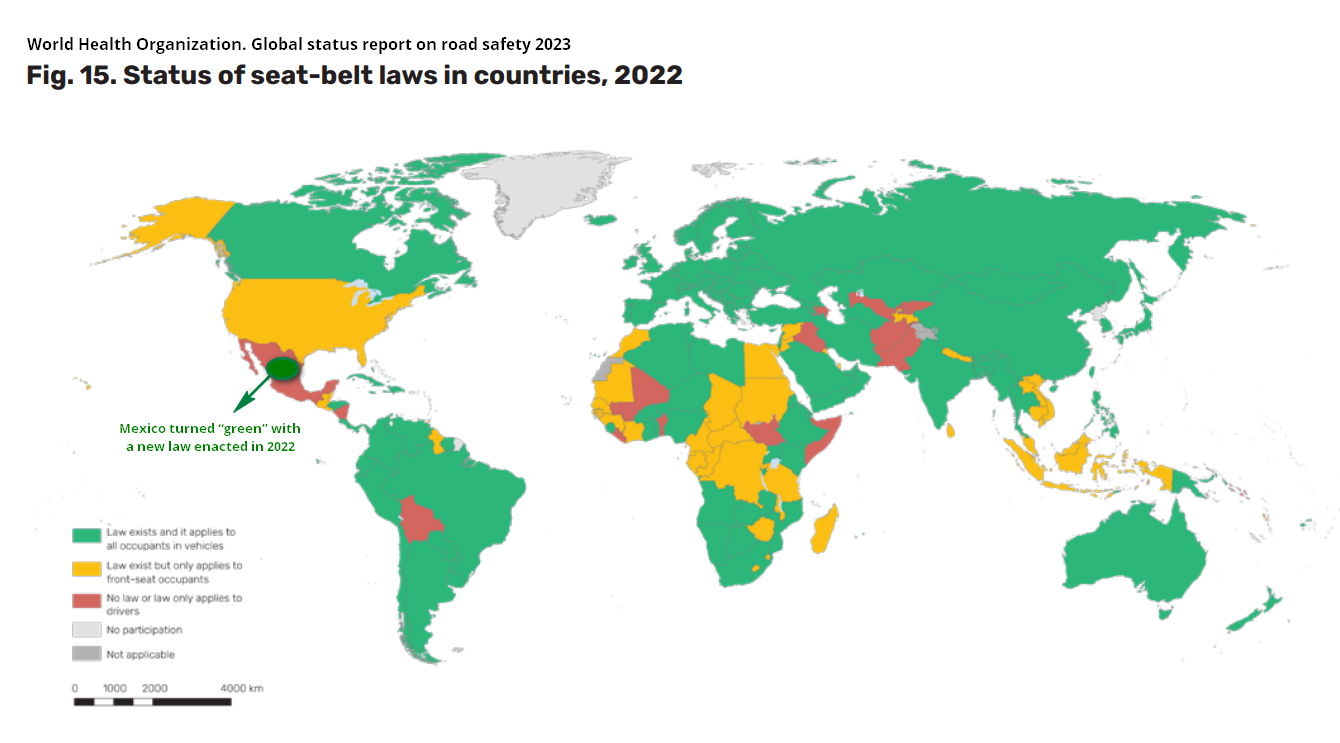

Note: As of January 2024, the map is no longer accurate because, for example, in Mexico, a law was enacted in 2022 that made seat belts obligatory for all passengers.

The Facts:

The idea of the usefulness of seat belts for the prevention of deaths and serious injuries in car accidents seems to be indisputable among public health officials. For example, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advocate the use of seat belts, claiming that they “reduce serious crash-related injuries and deaths by about half” and reportedly “saved almost 15,000 lives in 2017,” based on U.S. data. Global status report on road safety 2023 by the reputable World Health Organization (WHO) warns, “Failure to use seat-belts is a major risk factor for road traffic deaths and injuries among vehicle occupants,” and commends seat-belt mandates, shown in the image above.

If we look up some of the evidence cited, seat belts were tentatively found to reduce the risk of overall injuries, but a subgroup analysis by the location of the critical injury gave inconclusive results, meaning that some types of injuries may actually be unprevented by seat belts, such as head, neck, or chest trauma. This does not necessarily mean seat belts don’t work. In fact, seat belts are associated with an abdominal injury of their own, even though the risk of overall abdominal injuries decreases, as the aforementioned subgroup analysis suggests. The physics of seat belts in simulated car crashes make it visual how they work: by restraining the user, they won’t let them move forward after the car has crashed against a barrier, which hopefully saves lives. A 2011 analysis based on WHO’s data from 46 high-income countries showed that seat-belt compliance was strongly associated with road traffic death rates. There is room for speculation about causality here, however, as these are high-level data that do not preclude the existence of a third variable that improves both seat-belt compliance and motor vehicle accident statistics, thus remaining masked in the analysis.

A recent study by Cochrane, the world’s leader in synthesizing medical evidence, went unnoticed in the news media (see our research). This analysis looked at the effectiveness of activities promoting the use of seat belts. The activities studied included various education formats offered in sites such as workplaces, schools, or health care organizations, and a couple of trials investigated in-vehicle data monitoring and alert systems, with the majority of data collection conducted in the US. Cochrane has already published a useful summary of this study for the general public, which concluded that they “found some evidence to suggest education-based (behavioural and health risk appraisal (HRA)) and engineering-based interventions may promote seat-belt use in early and late adolescents and adults; however, we are not confident in the current evidence.” Zheln has reviewed their entire scientific report and confirms that this statement is accurate. To elaborate a bit on what exactly Cochrane did in this study, they looked at 15 randomized trials encompassing over 12,000 participants but were unable to combine these data due to their very mixed nature, so they ended up looking at each trial separately. It’s also of note that all 15 trials had a high risk of inflated findings, but that was more of a limitation of the study setting than a failure on the researchers’ part. Importantly, none of the trials reported on crash-related injuries or deaths.

The best takeaway from this complex picture is probably that our understanding of how the seat belt, or rather, seat-belt promotion works in practice is still quite vague. A previous study found modest but positive evidence of the effectiveness of mass media campaigns in increasing the use of seat belts. A US-based analysis found a median increase of 33 percentage points in observed seat-belt use after the enactment of seat-belt enforcement laws. With all these measures in place, seat-belt use is still far from universal: its pooled global rate, as of 2020, was at about 40% for drivers, 35% for front-seat passengers, and 10–15% for rear-seat passengers. We can also clearly see how the evidence in which the effectiveness claims are grounded is predominantly US-based.

The Evidence:

- Public health organizations like the CDC and WHO advocate for seat-belt use, claiming they reduce crash-related injuries and deaths by about half and save thousands of lives yearly.

- Evidence on seat-belt effectiveness is inconclusive for some types of injuries – they may prevent overall injuries but not certain ones like head, neck, or chest trauma.

- Car crash simulations show how seat belts restrain occupants and prevent them from moving forward during an accident.

- Analysis of WHO data associates seat-belt compliance with lower road death rates across 46 high-income countries, but causality is speculative.

- A recent Cochrane review found some evidence that education and in-vehicle alerts may promote seat-belt use in adolescents and adults, but the evidence is not very certain.

- That Cochrane review looked at over 12,000 across 15 randomized trials but couldn’t combine the data due to heterogeneity. None of the trials measured crash-related outcomes.

- Other analyses found positive impacts of media campaigns and laws on seat-belt use.

- Despite promotion efforts, seat-belt use rates remain low globally – around 40% for drivers, 35% for front passengers, and 10–15% for rear passengers.

- Most evidence on seat-belt effectiveness comes from the U.S. context.

- In summary, our understanding of the real-world effectiveness of seat-belt promotion is still quite vague.

The Research:

Notes

- If you want to contract Zheln’s services or simply reach out, do send us an email. We can do anything that touches the realm of health research: from running a hardcore meta-analysis from scratch to publication, through holding an educational tutorial session for health professionals or the public, through speaking at an event or writing for your newspaper. The only thing we don’t provide is medical advice; but, we do provide medical evidence.

- This post was created by a team of researchers and journalists with the help of multiple generative AI tools. Please refer to the video bibliography for more information.

- Full changelog of this page is available.

- The original Zheln whitepaper is available as a preprint.

- Follow Zheln on Threads and Instagram.

- Donations are accepted via GitHub Sponsors.

Citation

Zhelnov P. How Seat-Belt Promotion Works. Zheln. 2024 Jan 25;2(1):t8e3. URI: https://zheln.com/thread/2024/01/25/1/

| « Previous Post | Next Post » |

Let me know what you think of this article on Twitter @drzhelnov!