Picking Therapies for Liver Cancer

How can doctors know which cancer treatment is better?

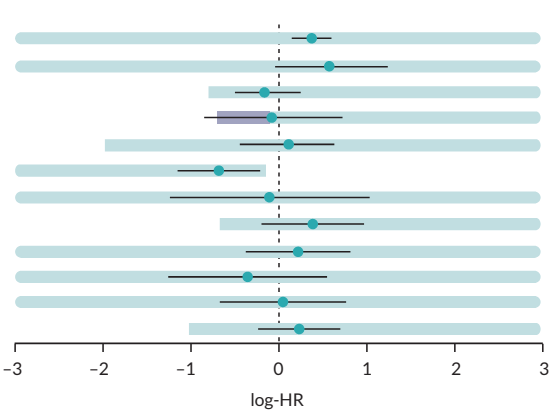

After reading this post, you will be able to understand this image:

The Facts:

A major medical study published in December 2023 challenged a common assumption about the best way to treat cancer. Researchers compared multiple treatments of early-stage liver cancer, including surgery, irradiation, chemotherapy, and a newer technique called high-energy destruction or ablation. Using cutting-edge statistical methods, they ranked treatments based on patient survival rates and cancer recurrence levels, accounting for statistical variation and study quality.

Surprisingly, the study found that completely removing tumors through surgery – long seen by cancer specialists as the “gold standard” – is no better than less radical options, like ablation, while still leading to more adverse events, including postoperative complications, major complications, and serious pain requiring painkillers.

Ablation is the destruction of body tissues using high energies, like heat, microwaves, or laser. It’s often paired with chemotherapy or radiation treatments. The figure above is usually called a “forest plot,” but we’ll use a more practical metaphor: Imagine that each black horizontal line in the image is a track runner, representing a cancer treatment, and the vertical dashed line is the finish line. The blue dot is the runner’s head (the estimated effect from the trials; in this case, overall survival), and the line is the span of the runner’s step (the probability range of the effect estimate, a so-called credibility interval). Our runners are moving from the right to the left, striving to cross the finish line, as in this running track close-up:

The positive effect is expressed as a negative number because it means fewer bad events (e.g., deaths), versus “standard therapy” (e.g., radiofrequency ablation). The runner who is the first to cross the finish line completely (with both the head and the feet) becomes the winner. This study attempts to challenge the winning treatment under various statistical conditions, trying to answer the question: Are we sure it is truly better than standard therapy, not incidentally? Maybe the trials generated this spuriously outstanding performance because they were biased, just like a runner suspected of doping.

As investigators, we artificially increase and decrease trial results to see how much change the calculations can tolerate before the best-case scenario switches to some other treatment option. Imagine that our runners are riding slugs, represented by light-blue bands, which show the extended probability range that takes trial quality into account (so-called invariant intervals). The slug needs to drag their entire slimey body beyond the finish line before the rider can complete the race. Can you now see which treatment is winning?

Spoiler alert: the winner is the 6th slug from the top, representing radiofrequency ablation combined with the implantation of radioactive iodine-125 into the tumor. The head, the feet, and the slug are all across the finish line, so we can be pretty certain of the trial data.

Now, look at the 4th band, with the gray bar? That rider has real promise but got ahead of their own slug, which is against the rules, and was disqualified. This 4th line is microwave ablation, and it has a chance of competing with the top-choice procedure, radiofrequency ablation plus radioactive substance, but only if more high-quality trials show its effectiveness.

By the way, the traditional hardcore surgery (liver resection) is the 3rd line from the top – can you now tell how well it performed versus radiofrequency ablation? This example shows how the latest scientific methods can challenge clinical assumptions and help pick better options among various possible treatments based on the bulk evidence from human trials.

The Evidence:

- An over-200-page research report was published in December 2023 that explored evidence on novel treatments of early-stage liver cancer, otherwise known as hepatocellular carcinoma. With respect to this particular cancer, early-stage means the size of the neoplasm less than 3 cm and no distant tumor growth.

- Using advanced statistical techniques, developed over the last 25 years (called network meta-analysis), the researchers compared multiple treatments, including high-energy destruction (ablation, laser), irradiation, chemo, surgery (liver resection), ethanol and acid injections, and other dangerous stuff. Additionally, they were able to account for the quality of scientific data by forecasting the impact that it may have on the numbers (using a technique called threshold analysis).

- The scientists ranked treatment procedures by their efficacy and calculated the amount of numerical change needed to “overthrow” the top-performing procedure in the “league table.” Two groups of metrics were used to assess efficacy: patient survival (overall and progression-free) and tumor recurrence (overall and local).

- The evidence suggested unusual conclusions that contradict clinical judgment or common-sense tumor biology; the most radical treatment, liver surgery, commonly thought to be the most effective treatment due to the full removal of the neoplasm, performed no better than more “dirty” techniques such as radiofrequency ablation. This conclusion stood even when study quality and statistical variation were taken into account.

- Additionally, the implantation of radioactive iodine-125 (brachytherapy) boosted the effect of radiofrequency ablation, based on overall survival, and was forecasted to improve overall tumor recurrence rates in future trials. Microwave ablation is a promising competitor of radiofrequency ablation and could outperform it by overall survival and local disease recurrence in future trials.

- This evidence illustrates the state-of-the-art scientific techniques employed for picking the best treatment from a range of possible options, as well as selecting the most promising candidates for future studies.

The Research:

Notes

- If you want to contract Zheln’s services or simply reach out, do send us an email. We can do anything that touches the realm of health research: from running a hardcore meta-analysis from scratch to publication, through holding an educational tutorial session for health professionals or the public, through speaking at an event or writing for your newspaper. The only thing we don’t provide is medical advice; but, we do provide medical evidence.

- This post was created by a team of researchers and journalists with the help of multiple generative AI tools. Please refer to the video bibliography for more information.

- Full changelog of this page is available.

- The original Zheln whitepaper is available as a preprint.

- Follow Zheln on Threads and Instagram.

- Donations are accepted via GitHub Sponsors.

Citation

Zhelnov P. Picking Therapies for Liver Cancer. Zheln. 2024 Jan 11;52(1):t6e1. URI: https://zheln.com/thread/2024/01/11/1/

| « Previous Post | Next Post » |

Let me know what you think of this article on Twitter @drzhelnov!